For a while now I’ve been thinking about comic artists and writers of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. They were people directly affected by the wars and violence of their time. Some went on to create truly amazing and grisly horror and crime comics, in part reflecting on these experiences. Others, faced by the mechanized violence on a previously inconceivable scale, created heroes who did not kill. The creators of these characters and the writers and artists who fleshed them out have often been presented as products of a simpler, more naïve time, erasing the violence of wars, genocide, anti-Semitism, internment, segregation, lynching, occupation, colonialism, sexism, and so many other things in their lives. We create this past as our Eden and so don’t wonder why people in these circumstances and people who had seen war in societies completely mobilized for war would create heroes who do not kill. We do so ignoring both history and our own particular relationships with violence now–the distance with which wars can be fought; the distance some creators and readers can have from war; the distance people not living in areas in civil wars, occupations, or targeted by drones, suicide bombers, mass shooters or angry people with an ideology and a truck can choose to have. And so we can have idealized, distant ideas about just how easy it is to kill and ideas about how killing solves problems. We can act as if the only “realistic” consequences a superhero story can have are death or killing. And we take these superheroes and believe that they should kill, that the fact that they do not kill needs explanation and caveats.

The plot of Man Of Steel (2013) is unpleasant to me not because Superman kills Zod—in an extremely intimate, hands-on manner—but because the whole film’s plot is structured to justify this moment. It becomes the point. It answers the question director Zack Snyder and screenwriter David Goyer dare to ask: Why doesn’t Superman kill? As if not killing needs more of an explanation than killing in a world not entirely populated by genocidal psychopaths. As if killing were the norm and people must be taught not to kill, no matter the fact that people have to be trained to kill in war and even serial killers work themselves up to it.

Snyder explains why he and Goyer decided to have Superman kill in Man Of Steel (2013):

The why of it was for me [is] if it’s truly an origin story, his aversion to killing is unexplained, it’s just in his DNA. I felt like we needed him to do something just like him putting on the glasses or going to the Daily Planet, or any of the other things that your sort of seeing for the first time that you realize becomes his sort of his thing. I felt like if we could find a way of making it impossible for him, you know “Kobayashi Maru“–totally no way out–I felt like that could also make you go[,] “Okay, this is the why of him not killing ever again.”

He’s basically obliterated his entire people and his culture, and he is responsible for it, and he’s just like[,] “I can’t. How could I kill ever again?”‘…but again you will always have it in the back of your mind this little thing [of] how far can you push him. If he sees Lois get hurt, or if he sees his mother get killed, you just made a really mad Superman that we know is capable of some really horrible stuff when he wants to be. That’s the thing that is cool about him, I think in some ways; the ideas that he has the frailties of a human, sort of emotionally, but you don’t want to get the guy mad.

“I wanted the movie to have a mythological feeling. In ancient mythology, mass deaths are used to symbolize disasters. In other countries like Greece and Japan, myths were recounted through the generations, partly to answer unanswerable questions about death and violence. In America, we don’t have that legacy of ancient mythology. Superman…is probably the closest we get. It’s a way of recounting the myth.”

While I agree with Snyder that superhero stories are mythic, this is a peculiar arc to follow, especially for a hero. It seems more in keeping with the heroes of Fletcher Hanks–in which cities are destroyed, thousands die and antiheroes Super Wizard Stardust or Fantomah provide vengeful, vindictive justice in the end. You know, now that I think about it, Snyder and Goyer might be just the right team to make a Fletcher Hanks movie. But it is interesting to me how important it seems to them for Superman to kill. Readers and the people of Metropolis don’t need to see Superman lose control to fear what he could do if he did lose control.

In some ways Superman is stealing Wonder Woman’s thunder in Man Of Steel. His killing of General Zod is a visual reference to the time Wonder Woman snapped Maxwell Lord’s neck—because she knew Superman couldn’t. Wonder Woman was written into an impossible choice, but at least it was in recognition of Superman’s character. And she suffered the judgment of her superfriends Superman and Batman–as well as the world’s–for murdering a man.

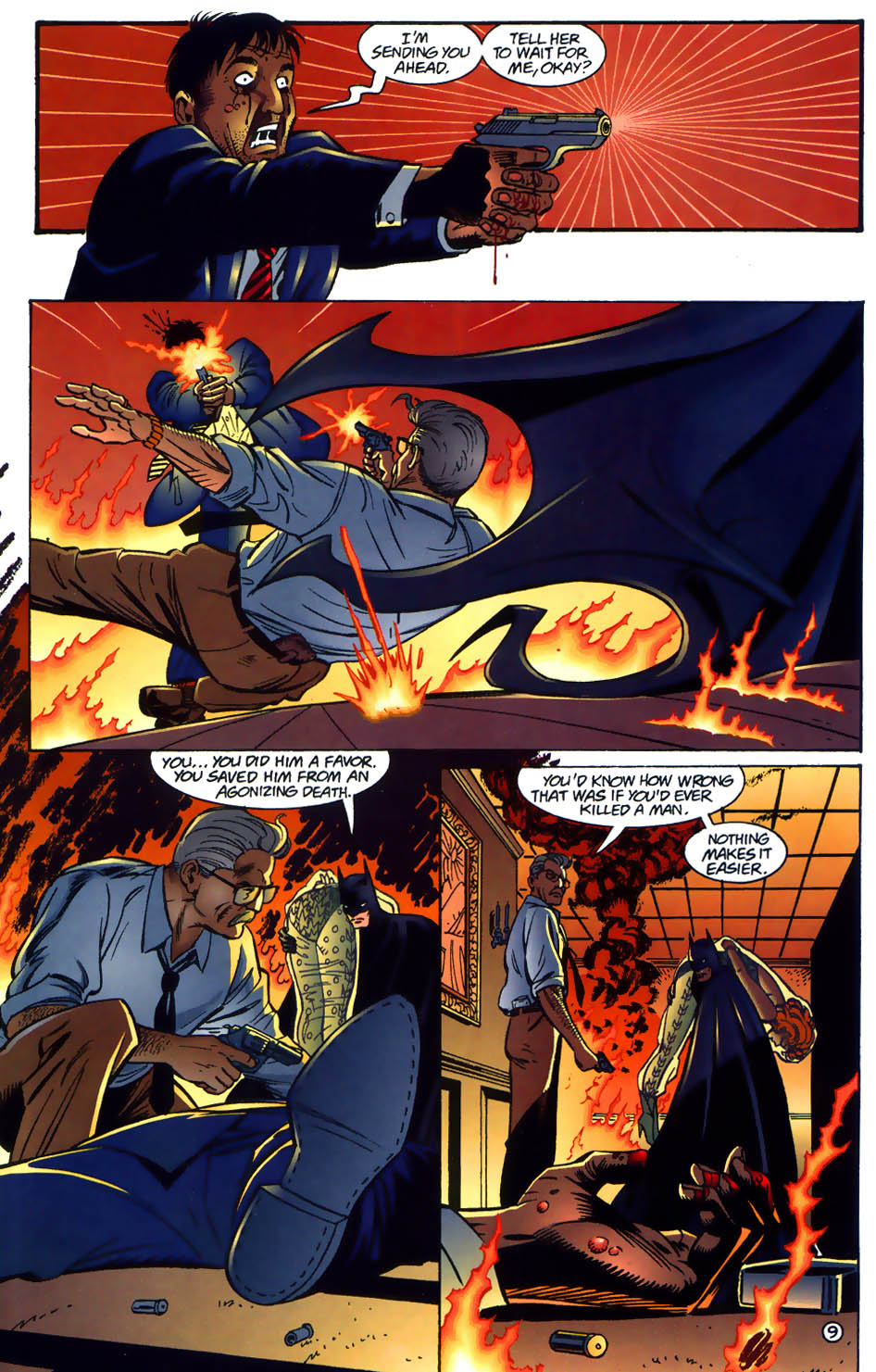

We ask the same thing about Batman, “Why doesn’t Batman just kill the Joker?”–not recognizing that “just” conceals a lot. The question ignores Batman’s motivation, that after seeing his parents shot dead in front of him he never wants that to happen to anyone again. And, again, the question presupposes killing easier and more consequence free than it usually is. Even Batman, the world’s greatest detective, can make the mistake of believing it. After Commissioner Gordon shoots a man in self-defense. Batman tells Gordon that he did the right thing. Gordon tells Batman that he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

For Batman, killing and who he would be after he kills someone are still theoretical*. Killing changes a character, regardless of how you feel about Snyder and Goyer’s Superman; Wonder Woman killing Maxwell Lord; or Batman killing Joker.

And that brings me to two comics that are very much about how characters are changed by killing: Ed Brubaker, Sean Phillips and Elizabeth Breitweiser’s Kill or Be Killed (Image, 2016-ongoing)** and Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata’s Death Note (Viz, 2003-6)***. The protagonists in each are haunted by a supernatural being. Both make deals with death, though very different ones. Both are vigilantes who kill criminals, by very different means.

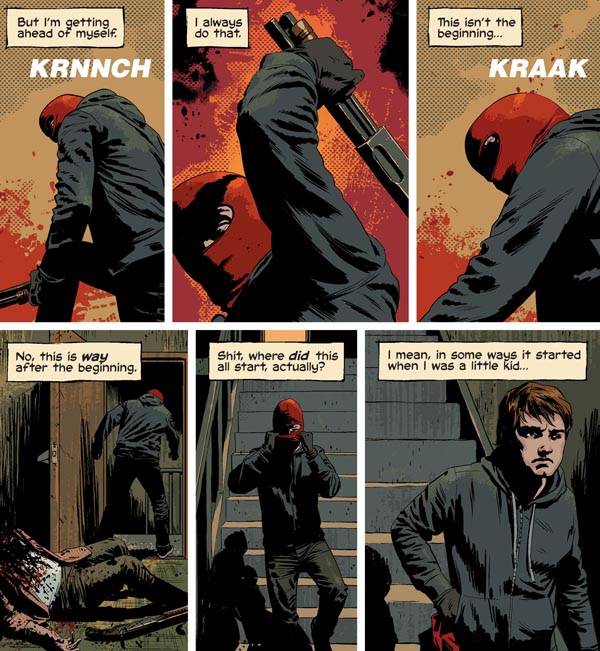

In Kill or Be Killed, Dylan is a depressed graduate student who is stuck in a rut in his studies and stuck on his roommate’s girlfriend, Kira. He’s been sleeping with Kira. Dylan tries to kill himself one night after overhearing Kira and his roommate discussing him, but he is saved by a demon who offers him a choice.

Dylan can kill someone else or die himself. For each person he kills, he gets one more month of life. Dylan at first thinks he imagined the encounter with the demon. He starts hearing the demon taunting him. When he becomes terribly ill, Dylan finds someone he believes deserves to die and kills them. Dylan’s fever disappears. His new life, though, gets in the way of his old life. He needs to research potential targets so he can keep on living. He needs to plan his hits. He needs to patrol the streets late at night.

Dylan’s killing is incredibly damaging to him, but he starts to see himself as something like Batman. Like Batman, Dylan has a bad relationship with the police. Like Batman, he is depressed and angry. Like Batman, he externalizes his anger. But while Batman risks his life to save the lives of others Dylan kills to save his own. He tries to hold on to the justifications the demon gives him, even as they poison him. Is the demon his own curdled entitlement, resentment and anger? Is the demon his depression? Is he terribly, physically ill and hallucinating? Is the demon the act of killing itself? Is it his way of avoiding his own culpability? Is it real and if so, is it lying to him?

Whatever it is, the demon tells him he is seeing the world as it is and Dylan begins to believe it. Corrupted, Dylan begins to see the world as corrupt. And he begins to see everyone as a potential target.

Kill Or Be Killed captures something here, something messy—white male depression, white male anger, the sense that if the right person or group of people is eliminated, everything would be like it should be. The sense that the world should be some way that it isn’t. But the book is messy itself, dragging in the downsides of its influences, vigilante movies like Death Wish, where the solution to encroaching non-whiteness and fickle, treacherous white women is for straight white men to listen to demons and arm themselves.

Death Note is much clearer in its presentation of the damage being a vigilante does to Light Yagami. As the story begins, Light is studying for his admission exam to a prestigious university. His life is very different from Dylan’s. Light is serious about his studies. He is sociable and popular. He is recognized as a genius. And he has a drive to help solve crimes, following in the footsteps of his father, National Police Agency Chief Soichiro Yagami.

Light finds a notebook on the ground outside his school one day with the words, “Death Note” written on it. Instructions inside describe how to use the notebook to kill people. If you write down the name of someone while looking at their face, they will die of a heart attack. If you write in a time and a cause of death, your victim will die in that manner at that specified time.

Like Dylan, Light Yagami encounters an infernal being that only he can see, Ryuk, a shinigami / God of Death. Unlike Dylan’s demon, Ryuk does not push Light to kill other people. Ryuk is just bored. Nothing is happening in the shinigami realm. Most shinigami spend their time gambling or sitting around. Ryuk drops a Death Note into the human world assuming that someone won’t be able to resist using it, thus allowing Ryuk to enjoy the ensuing hijinx.

Death Note seems to describe a perfect means of killing without any repercussions. What could be more distant–physically or emotionally–than writing a name in a notebook? Light keeps the Death Note, but he doesn’t test it until he witnesses a man harassing a teenage girl. At first, Light is frightened by what he has done. But after five days of writing in the names of criminals he sees in the news, he becomes inured.

Like Dylan, Light believes the world should be a way it currently isn’t. Unlike Dylan, Light is not resentful. Light is ambitious. He maintains his passion for justice, but it becomes warped. He plans to use the Death Note to perfect the world. Light wants people everywhere to know that they are being judged by someone with the power to kill them. He will eliminate crime by killing criminals and by letting everyone know that if they commit a crime they will die. He knows that criminals are a fearful and superstitious lot, but more, he believes that most people secretly agree with his actions. And as his killings continue people begin to post their support online. They call him, “Kira / Killer” and some even worship him****. And Light / Kira declares he will be the god of this new world, because he has the power to kill anyone at any time.

Ultimately, Light becomes more invested in outwitting the international task force created to stop him than in creating his new world. Eventually, he crosses his own line and kills only to protect himself. By then, though, he blames the task force for this death. If they had left him alone, he wouldn’t have had to kill innocent people. Ohba and Obata underscore the change in Light by having him revert to his earlier self. One of the Death Note rules is that if the owner of the notebook ever renounces possession of it, they lose all memory of the notebook, the killings associated with it, and the shinigami. As part of a scheme to outsmart the task force charged with stopping Kira, Light renounces the notebook and reverts to who he was before—smart, caring and dedicated to catching a killer.

Death Note is much clearer about the desires for easy solutions, like just writing down a name to erase a life we might find problematic. Or the willingness to pay the price of other people’s lives for a new world we want to create. Dylan is more Walter White / Heisenberg in Breaking Bad–probably passive-aggressive hostile before he became very actively aggressive-aggressively hostile. Light is a Classically tragic figure. He wants to do the right thing with his exceptional talents. He aspires to be a god and perfect the world and it ultimately and ironically destroys him. Light acts as a god of death, but he cannot be both a god and a human being. Ryuk even repeatedly implies to him that something terrible happens to humans who possess a Death Note. Not because Ryuk will do anything or there is a ritual price, but because killing like that destroys people. But Light filled with fervor and hubris, never asks Ryuk more about it. Light has no demon to blame but himself and the temptation of killing to perfect the world. I just wish that Dylan had no demon to blame but himself, too.

*I am aware of Batman’s early appearances and this. And I’m aware of Superman’s years when he didn’t necessarily save everyone. But both characters came to be defined by their refusal to kill and it’s that refusal that is being contended with and reversed in our dark age of comics.

**As with all Brubaker, Phillips, Breitweiser collaborations, single issues of Kill Or Be Killed come with essays in the back. Some of them are by Devin Faraci this time, so you know.

***Why, no, I haven’t been able to bring myself to watch Netflix’s adaptation of Death Note. On one hand, the idea of Willem Dafoe as Ryuk is really appealing. On the other hand… well, everything else.

****Kind of makes you wonder about Dylan’s girlfriend, huh?

~~~

Carol Borden cannot advise you strongly enough to never use a Death Note if you find one on the sidewalk. Also, special thanks to Mark D. White for the Detective Comics #696 scan. She really appreciates it!

Categories: Comics